SUPREME ARCHITECTURE — Alex Knittle’s LOVE Letter To Philadelphia

TEXT: STUART GOMEZ_

_

Alex Knittle’s Supreme Architecture takes its name from the Wu Tang Clan, played in the intro. In a voiceover, RZA philosophizes with his classic brand of Shaolin street sermonizing, “For the Supreme Architecture, that’s the one who comes with the most illest creation… the illest ideas.”

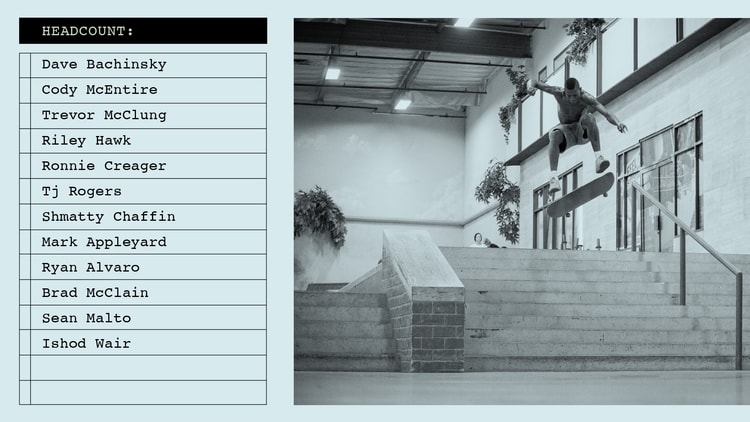

The title fits perfectly for the thirty minutes of Philly street life that follows. Knittle has a keen eye for the absurd characters and behavior that revolve around skating in the city, and he casts a loving glance towards the buildings and plazas that define the cityscape. Supreme Architecture is, in some ways, an outsider’s view of Philly. But one that Knittle developed by embedding himself in the scene and appreciating every aspect as if he was born there.

Knittle grew up two hours away in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and started coming to Philly as a kid. In 2009, he skated LOVE Park for the first time (previously, LOVE was fenced off and considered unskateable). The effect was transformative.

Seshus interruptus in Harrisburg, PA. Photo by Andrew Marshall.

As Knittle made more trips to Philly, he started to piece together the contradictions of criminalizing skateboarding in the city. “The police and city council spent so much time and money policing skateboarders while there were definitely people who needed more attention,” Knittle says. “Like dudes selling hard drugs or people that needed to be in mental hospitals.”

Over the years, the city had made decisions that effectively focused on oppressing skateboarders but didn’t necessarily positively impact non-skateboarding citizens. Turning LOVE Park into Fort Knox—with the modern armor of skatestoppers, prison yard fencing, and shiny new No Skateboarding signs—gave Philly’s most storied skate plaza a maximum-security vibe, and that atmosphere was hard to shake.

Knittle, like many others who viewed the skateboarding ban as an overreaction and a sort of death of a beautiful era of skating, cites a particular episode as indicative of the city’s irrational mindset at the time: DC Shoes offered Philadelphia one million dollars to maintain LOVE for a period of ten years, and the city declined the offer in a dishearteningly shortsighted decision. What followed was a reported $800,000 shelled out by the city for LOVE’s renovation, rendering it “unskateable.” The six-figure price tag didn’t cover patrolling the plaza or the upkeep of replacing all of the benches and skatestoppers that were eventually ripped out (skaters love a good challenge).

Alex Knittle. Photo by Andre Marshall.

Speaking with Knittle, he brings up Paine’s Park—another example of Philly’s anxious decision-making: “The city spent close to five million dollars to build Paine’s Park. If you ask any local, Paine’s sucks compared to what we had at LOVE. When you compare the 5 million dollar price tag of Paine’s to Reid Menzer Skatepark in York, which cost around one-fifth of what Paine’s cost, you realize that there was a lot of money wasted for a park that isn’t even that good.”

LOVE Park is captured in its final days in Supreme Architecture, in a sequence incorporating shots of the plaza’s ultimate destruction set to Curtis Mayfield. The images are sad, but the effect isn’t meant to be somber. Like the video’s title, the final LOVE sequence has a double meaning. If the ecosystem at LOVE was left alone—if skateboarding hadn’t been criminalized and the mini community of non-skaters, skaters, and occasional police intervention had continued apace—it may have just evolved naturally, blending with the overall chaos of city life. Instead, it stands as a monument to an endless struggle between the city and skateboarders. Renewal comes in many forms—even supreme architecture can be razed.

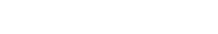

Supreme Architecture features Evan Goss, Donny Hixson, James Britton, Dylan Jeffers, Stephen Carty, Jason Klotz, Ryan Miller, John Tuck, Nate Cabigting, Jeremy Murray, Kevin Taylor, Tony Montgomery, Stanley Mowry, Ronnie Gilbert, Tyler Murray, Tyler Claus, Will Tozer, Mike Wojcik, Beau Sluder, Zach Plank, Adam Vizy, Mike Rankine, Omar Alverio, Kyle Nicholson, Sean Korney, Chris Landry, Dave Platowski, and Anthony Rosado.

The following is a condensed version of our interview with Alex Knittle.

Tell me about Supreme Architecture.

It’s a skate video I started filming in February 2014 after I moved to Philly. I got a studio for $375, which was dirt cheap for Center City, and I was just trying to make an HD video because everything coming out of Philly at the time was pretty much filmed on VX1000. There were a lot of cool things I was seeing in Pyramid Country videos and Bronze videos that weren’t really being done in HD, so I guess I was trying to do something that was a mix of HD and weird analog effects.

What inspired you to start this two-year project?

I was traveling back and forth between Harrisburg and Philly and just realized that I could live in Philly with out a car—I could skate everywhere. There are so many people I can skate and film with; you could pretty much be productive whenever you wanted.

Out in Harrisburg, PA—about two hours away from Philly—the skate scene is not big at all. It’s hard to get people motivated to get things done. The job I had in Harrisburg was pretty flexible, so I would go to Philly for a weekend or three days at a time. It was perfect timing because LOVE Park was fully skateable, especially if you went after 10:00 p.m. And my studio was like five blocks from LOVE.

Did you eventually start to feel like a LOVE local?

I definitely wasn’t as hardcore as a lot of the Sabotage guys that were there. It was really hard to be productive at LOVE during the day just because so many people were going there. Skaters, random people hanging out, crackheads… and then the cops would come every hour. It seemed like every time I pulled out my camera the cops woulf come and I’d have to grab my gear real quick.

To actually get anything done you had to go at night, which was risky.

Let’s talk about some of that local flavor. You did a great job of portraying all of that randomness. I love the recurring shot of the guy smoking and bouncing his head.

That guy was so funny! There was a contest down at Paine’s Park and he was just some random dude hanging out. I think he was either selling waters and he was just partying with us. It was such a good time!

Was that always part of your vision for the video—to incorporate a lot of those street scenes?

I wanted to incorporate a lot of the things that people want to look away from, and then also sort of engage with these characters a little bit. Almost all of the homeless that are in there, and some of the performers who are playing music or dancing, I’d buy them a bottle of water or a banana or throw them a couple of dollars if they were a performer.

Like, with the drum line sequence: those are the sounds you hear when you’re walking around the Philly streets.

It worked out so well with the skate footage, too. Was there a message you were conveying with the intro? It seemed chaotic, almost like a “social unrest montage.”

Right. It was definitely just the stuff I was seeing, like coming from where I grew up in Harrisburg to Philly—everything just seemed really absurd. You have a lunatic walking down the street doing something completely crazy, and people just ignore it like that’s just everyday life. You have all this crazy stuff going on in the city, and then you have this group of people just trying to do something really positive and making the most of the street spots that are available.

Did you initially want to highlight that street element? That there are people at the spot who are homeless, on drugs, or maybe have a mental illness…

That’s what comes with it. The people are right next to you when you’re trying to do a line. They’ll come right up to you and they’ll talk to you. When you actually get to know these people, you start liking them.

One of the guys, Joe McPeak, he would hang out at LOVE and get wasted off of mouthwash everyday. One day, I had a conversation with him. Joe was just a normal person that just got thrown off of his path a little bit. Joe was a loudmouthed dude: he would always come up to you and try to bum a cigarette, and he was always cracking jokes. All the skateboarders befriended him and would bring him clothes, hats, and waters.

Stanley Mowry. Photo by Andre Marshall.

How did you decide on how you titled every clip? I thought it was an interesting choice to label the skaters’ names every time they had a clip in a montage.

It just kinda worked out that way. At the time I was watching Static I [2000], the Northeast sections, and it was kinda the same thing. I was just really hyped on that at the time. When Static IV and V [2014] came out they kind of did the same thing too. And some of the dudes in Supreme Architecture are unknown outside of Philly.

What made you choose the RZA quote for the title?

It goes with the Wu Tang song in the intro. I thought it was cool. To me, it means being able to create whatever you want. Having this vision of what I wanted to create and it coming full circle, it actually ended up being what I wanted to make. Just inspiration to go after what your vision is.

Which came first?

The song came first and then I was trying to figure out what to name it. Then it just made sense because of all the architecture in Philly: City Hall, Municipal Plaza, LOVE Park. That was all really cool architecture at the time.

It’s sick that you were able to capture the last two years of LOVE.

Dude, I got so lucky! Growing up, I remember LOVE Park getting fenced off. It was kind of a big deal. 2009 was my first time there on a day trip to Philly. It just worked out with me getting a studio nearby.

For your first time at LOVE, what was the impact on you?

I was blown away! It was a crazy day: I got a flat tire on the way to Philly, it made our trip hours longer than it needed to be. I don’t remember anything else about going to Philly besides just being at LOVE. I don’t remember parking the car, I don’t remember leaving. I just remember being there and it being so awesome. It was fun to skate the flatground. The ledges were a little chunky, but…

Did you feel like an outsider at LOVE or did you feel at home pretty quickly?

No one fucked with me, but it was hard to get certain people to film for my video because I was new to the city and hadn’t put out anything really good. I definitely saw some locals giving other people a hard time, but as long as you’re cool and respect everybody else… just give everyone who’s been there the “right of way,” then you’re good.

Is that something you just knew instinctively or did you have to learn that after multiple trips?

I watched the LOVE Park documentary [2003] and I heard a lot of crazy stories so you just know you’re walking into something gnarly and you know someone else holds it down there. You don’t want to get in the way. If it snows, you wanna help shovel it. Definitely help out however you can.

When I was younger we wouldn’t go to LOVE because we thought it was unskateable. We would go to City Hall instead. In 2009, the word on the street was that it was cool to skate after 10:00 p.m.

What is your image of Philly now that LOVE is gone?

Man, it doesn’t feel the same after LOVE’s been gone.

Do you have another Philly project in mind?

I wanna make a short Harrisburg video because there’s a lot of good spots but no Pros ever come through here—there aren’t any parks close to here. No one’s ever made it out of Harrisburg and made it in the skate world. Harrisburg has a huge opiate/heroin problem—not much different than a lot of other places in the United States right now. Almost all of my friends that I grew up skating with ended up doing heroin, and obviously skating and filming stops being a priority.I’d like to put Harrisburg on the map and get people to wanna come out here and film.

Evan Goss. Photo by Andre Marshall.