Jacob Rosenberg’s Interview About His ‘Family Portraits’ Journey

Jacob Rosenberg and Mike Blabac at Blabac’s Family Portraits book release party, Los Angeles.

WORDS: Stu Gomez

For the release of his upcoming book Family Portraits, Mike Blabac teamed up with his friend Jacob Rosenberg to create a touching short film. The two are legends in photography and videography, respectively, with both playing enormous roles in shaping the emotional depth of contemporary skate media over careers which have spanned three decades.

Rosenberg cut his teeth under the tutelage of H-Street and Plan B Skateboards co-founder Mike Ternasky (1966-1994), and is responsible for the holy trinity of Plan B videos that kicked off the most progressive era in skateboarding: Questionable, Virtual Reality, and Second Hand Smoke. His transition from skate videos to documentary and commercial work is seamless, showcasing a finely tuned knack for storytelling that really separates his work from the pack.

Skaters of a certain age revere Rosenberg, and for good reason: We had never seen anything like those first three Plan B videos before and, in a way, they’ve molded us into the middle-aged skaters we are today. Thank you, Jake.

I really enjoyed “Family Portraits,” and I didn’t realize that you and Mike Blabac had such a deep history together.

You know, it’s funny—we don’t necessarily have a long history from the nineties. The last sort of “big” thing I did in skateboarding was make Second Hand Smoke for Plan B right at the end of 1994, and that’s right when Mike started working professionally and working in San Francisco as a photographer. So, we didn’t really cross paths—of course, I knew of him and his moniker “Blabacphoto.” It was just such an interesting way of presenting himself and I think it made him more of a “premium”-feeling photographer. But we didn’t really connect until I started to make Waiting For Lightning, and I started filming it in 2008. And I realized that he had all of the photos and he had all of the stories because he witnessed all of the amazing things that Danny [Way] did. And so we really met when I sat down to do a long interview with him in 2010 and we just realized that in skateboarding when you’re a photographer or a filmer, the same way that skaters could go to any town and meet someone and sleep on their couch because they’re instantly homies. I think for photographers it’s the same thing: you understand the patience and you understand the gaze and the love we have for skateboarding. We connected really deeply around 2010 and we’ve been super close friends ever since.

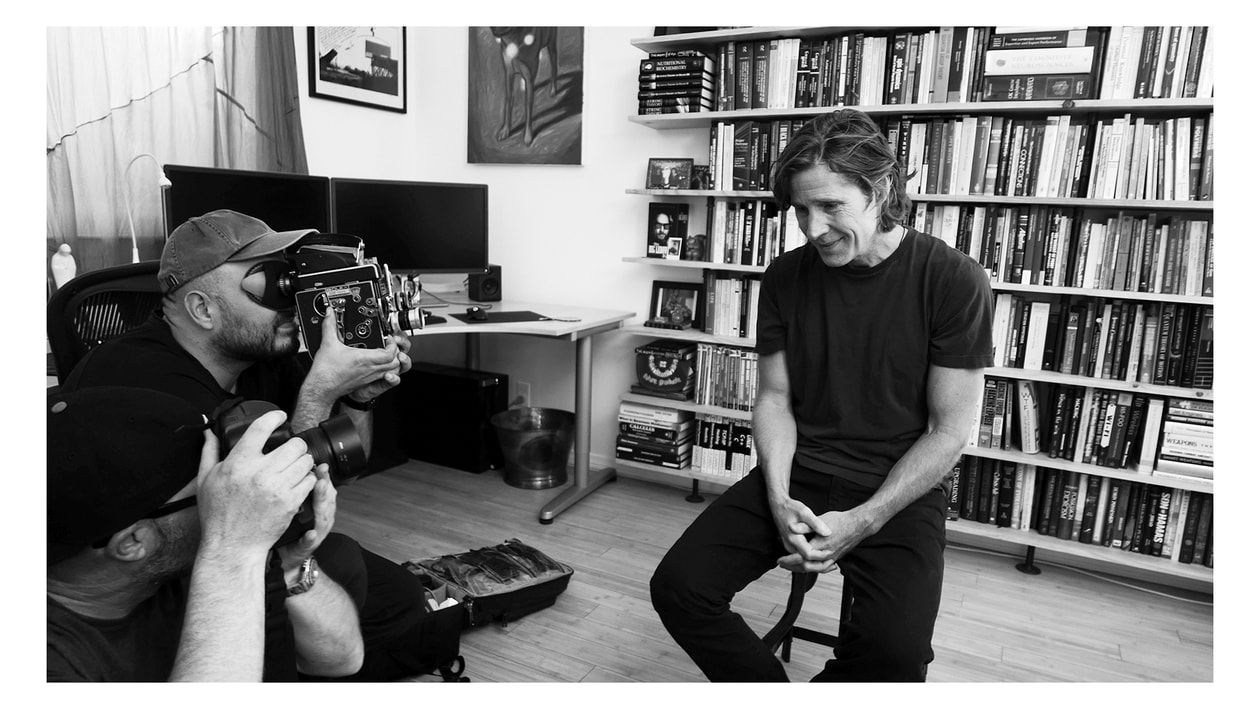

Rosenberg, Chico Brenes, and DP Guillermo Garza. Photo: Blabac.

When you first realized that you had so much shared experience, was there something specific about Blabac’s history that really clicked with you?

It’s interesting because one of his first gigs was shooting photos for Girl. And, of course, Mike [Carroll] and Rick [Howard] are guys that I have a very intense and close history with form the Plan B days. So the first connection was, “Oh my God, he worked with Mike and Rick in the early days of Girl,” and then filming Danny for the Plan B videos and him being around Danny for all of the progression that Danny was doing, that was another real alignment. In those days, you’re waiting a long time for someone to land a trick, but you’re not complaining about it. But if you were to complain, it would be with another person who has waited hours for similar tricks. But you’re not complaining because you’re not loving doing it—it’s the process. So we both knew what it was like to wake up in the morning and know that you had to film something, and wait for the skater to emotionally get in the right place to do it, and then you’re just committed to being there until it gets done.

So you both are pretty practiced with patience!

I think you have to be. That’s why I think that the great filmers and photographers really love the skaters and really honor the skaters and what they do. Because you can’t wait for it unless you really believe in the person that’s doing it and you really care about your subjects. Patience is just a component of the job. You’re willing to do whatever it takes and hang out for as long as you can because you want to capture that.

And it’s also the way that you’re capturing it. For a guy like Mike, I think he has a really extraordinary sense of composition and framing and feeling that his skate photography embodies.

Appreciating the skating is one thing, but do you feel like you’ve had to cultivate a sense of patience over the years? Or did it come naturally to you?

I was really young when I was making all those videos, and I definitely had to be patient. I was in it very intensely during those years and then I found that I didn’t have the patience for it at a certain point. When we were making Virtual Reality, that was a really challenging thing for me to face. I was kinda not as stoked when I thought about having to do it again. And part of that was [because of] Mike Ternasky passing away it was kinda what pulled me away from skateboarding in that moment. But I think that patience comes from caring about documenting it, and you have to have patience if you are trying to do something different. You know, I think about sometimes you are filming something and it’s taking a long time, so the way to keep yourself interested is to change your angle. And I think that’s sometimes a mistake, as a filmer. Sometimes I’d filming something as a follow, and then they wouldn’t land it for thirty or forty tries and I would get tired of following. So I would sit down—I have to because I feel tired—but the better angle was the follow. I think that that rigor is so integral to trusting your voice, but it requires the type of patience that we’re talking about. When you talk to Blabac about shooting some of those photos of Danny, he’s literally camped out at a place for five hours in one spot because that’s the best place to take the photo.

Wow, you’re the perfect person to talk to about skate filming! A couple of years ago I watched the documentary Film Worker and I got so stoked when you popped up on screen. You have a way of analyzing all these aspects of filming that most people wouldn’t consider.

Well, I was super, super fortunate. There were very few filmers from my era, who were my age. They were out there: some of them were in San Francisco; some of them were on the East Coast; and some of them were in LA. But my teacher, my mentor, Mike Ternasky, really, really thought about how a skate video was supposed to feel and how it was supposed to make you feel. And that was directly related to how you film the tricks and how you edit them to the music. I think that as I went to film school and I fell in love with cinema, and I started to have a more rich vocabulary in terms of understanding the mechanics of storytelling—with editing, and with visuals, and with a narrative that pulls you through—it’s made me understand why the videos we made were so effective. Or why, when I watch certain videos today, I feel nothing. Or why, when I watch certain videos, I feel everything. I was very lucky to be in the time that I was in, and I was also lucky to have some really painful and traumatic experiences to keep me in touch with my own emotions, in a way that not many other people my own age would normally be confronted with. Confronting those emotions through the videos that I was able to be a part of really taught me a lot about what works.

Rosenberg, pop shuv. Photo: Blabac.

And you were able to communicate that feeling to your audience…

I was able to understand that. The thing that I’m most proud of about the work that I’ve been able to do is that you feel it. There’s no Plan B video that you don’t feel. But that was the point. The point wasn’t to make a montage; the point was to make a feeling. And, again, the feeling is related to how you shoot the trick and how you put them together through music. Or no music, and that communicates something different, you know?

In Jeremy Wray’s [Second Hand Smoke] part, it was very hard to imagine how we would put that trick at the end of the part because it was such a long line. But to start that part with just skating and total emptiness, letting the biggest hammer be the first thing in the part which cues the music? That’s what I was chasing. That idea was a perfect snapshot: it’s so raw, you’re expecting there to be music at every turn, but now there’s not music? Wait, what’s going to happen? For me, it’s one of my favorite things that I’ve done in skating because you start leaning into this part like, “What’s going to happen? What’s going to happen? Holy fuck, he just frontside flipped Carlsbad!”

And that opener has been hugely influential. It seems to have been imitated a lot ever since.

I think the formula works, you know? There’s a lot there that I’m really proud of contributing to the conversation of skateboarding, like the rhythm of that part which I was doing really intentionally. But imitation is fine. I’m imitating! You know, I’m following the lead of things that I love. But imitate, then find your own voice in that imitation. Like, What are you trying to say?

J. Grant Brittain, Blabac, and Rosenberg. Photo: Garza.

With Virtual Reality, it felt like each skater was kind of treated as a character. I can distinctly remember Sean Sheffey and Rick Howard, in particular, having a strong tone for their parts.

Yeah, putting Rick James in Rick’s part! Again, that was the environment that Mike Ternasky cultivated. We could literally look at each other and say, “Dude, we should put Rick James in this part.” And we weren’t like, “That’s lame.” We were like, “Oh shit, that’s crazy! That’s great: it’s kinda funny, and Rick’s personality is funny.” So, then the choice of music actually was more about having a conversation about the skater than just cutting the music for the part. Which, to me, I think that’s what the Plan B videos really embodied—we shaped the personality of the skater through the editing and through the music. Those were pieces of personality that we put into those parts.

The longevity of your Plan B videos is really something else.

It’s amazing. I still get emotional when I watch them.

Garza, Rick Howard, and Mike Carroll. Photo: Rosenberg.

I want to jump back to Blabac and the “Family Portraits” video real quick. You guys really connected in 2010, but looking back now it seems like the collaboration was a no-brainer. Was there ever a project you guys talked about doing in the early days?

There wasn’t. You know, it’s interesting: Mike did his book, Art Of Photography, in 2009 but not a lot of skate photographers take the time to do books. Some skate photographers will do cool themes, or artistic-leaning photo books, but I think that having so many photos published in magazines people don’t instinctively think about collecting all their photos and putting them together. So, Mike and I became friends and he mentioned that he wanted to do a portrait book, and St. Archer came in and commissioned a book for him. They basically paid for the book and paid for supporting material around the book. He told me a year ago that he wanted to do this portrait book for St. Archer, and he left it really ambiguous like, “Let’s do something.” I think, from his standpoint, as friends we had this rich emotional connection so he asked me if I wanted to make a film. I was like, Yeah of course! And I told him I really want to talk about his family and I really want to interview his daughter. I think Mike looked at my storytelling and he looked at my heart, and he knew what I know about him personally. And I think by him asking me to be a part of it, he was giving me permission to go a little bit deeper and he was trusting me and do something that could be really meaningful.

That “family” feeling really comes through in the film, too. Sometimes it seems like Blabac is reconnecting with long-lost brothers or something.

You know, that was definitely the intention. It was like, once we agreed to do it I knew that I wanted to tell this very specific story of connection. So the hugs and the daps, and the closeness of the relationships was sort of integral to the story I wanted to tell: I wanted you to see frames of Mike hugging people; I wanted you to see frames of him shaking hands and talking so you could feel a relationship in the frames. The only way we could do that is to shoot people he knew and he was close to and had a connection with, and we wanted it to be a deep variety of people. On that same note, in order to let the vibes go even deeper there’s a big benefit to having the people we shoot also be people that I know from my time in skateboarding. So that when I see them and I’m behind the camera with my DP [Guillermo Garza], filming it, there’s a sense of “Oh this is cool, there’s a nostalgia here. Jake is here.”

We mapped out from San Francisco, through Ventura, into LA, and San Diego. There are some people… like Frank Gerwer: I know Frank, but we never really spent much time together. Or Wes [Kremer]: I know of Wes; I’ve never met Wes.So there were people that I didn’t have close relationships with, but Mike knew them so there was still that sense of connection. It was clearly about trying to capture this notion of we are going to all these different places with all these different people and all these different backdrops, but what you see is a human connection and a human relationship. And then if Mike can talk about his own journey and we mask that on top, you hear him talking about his journey and you see him with an undeniable family.

Did Mike choose all the backdrops for the photos?

We talked about it, based on the people. We knew we wanted to go to EMB because I spent a lot of my childhood there filming those guys: Karl [Watson] and Chico [Brenes] at Embarcadero. I did that for fuckin’ years! But most of the other people was out of necessity for where they were. When we saw Rodney [Mullen] it was like, “Yeah, I’m at home”; Tony Hawk, we met at the office; Grant [Brittain] we met at Grant’s house. For those things it’s about where Mike wants the portrait to be, and then in a couple of things I had a history there. And we went to a couple of other places—like where Hubba Hideout was, and the [SF] library downtown—to pick up some of those textures.

And Gerwer’s bike?

You know, it’s the same thing of Mike saying to me, “Hey, I really want you to make this film on me,” and me saying, “Well, I want to talk about your family and I want to interview your daughter.” And him being like, “Okay!” Mike said he really wanted to do this portrait of Frank, and Frank said, “I really want to do this thing on my bike down the street.” And then it just started happening! And Mike knows he’s not gonna tame it, but that’s also what he created. So if you’re Frank, you’re thinking Blabac is coming to take a portrait, I want to do something cool! Even though there isn’t a lot of surface conversation, there is a lot of internal conversations that make that magic happen—a lot of that comes from Mike.

Blabac, Garza, and Rodney Mullen. Photo: Rosenberg.

When you were interacting with everyone on the shoot, what was the feeling you had? Was it a nostalgic feeling, or did you feel like you were sort of reuniting with old friends?

It was a little of all of it. You know, I’ve kinda come to understand how I like to work when I’m telling stories and making documentaries, so there’s a part of my brain that’s focused on what I need to capture before I leave the location that I’m in. So I’m not so present that I can’t get those thoughts out of my mind, but I also looked at the trip as a way of affirming feeling from my youth and allowing myself to be nostalgic or be emotional. To just genuinely reconnect with these people, and look at them in the eyes, and hear them talk. I think as you get to middle-age and you start to look back, if you have the right people in the right places you can capture some of those things that were so intoxicating to you as a kid. I think there was a level of intoxication from seeing these people that mattered so much to me, and many of them still matter. A handful of them are still very close friends. There are people in there that really changed my life: people like Jim Thiebaud; Rodney; Mike and Rick; Karl; Chico. Those guys were around at a time when I was really trying to understand who I was. When I see them and I’m able to be myself, there’s a real sense of gratitude for the journey and them being able to be a part of it.

It is amazing that everyone involved in “Family Portraits” is still involved in the skateboard industry in some capacity.

I love contributing to the culture through my archive and through the insights that I have about skateboarding, but I’m not a part of it in the way that I look at all of those other people who are actually hustling and pushing to be part of that pulse. I’m like a finger on a limb, but I’m not the nervous system and I’m not the heart. I’m just trying to understand that I was involved in some really important conversations at an integral part of my life, and as I’ve grown I’ve learned the true significance of the culture and really what it gave me as a human. And I really just want to give back the intellectual depth of the conversation surrounding skateboarding.

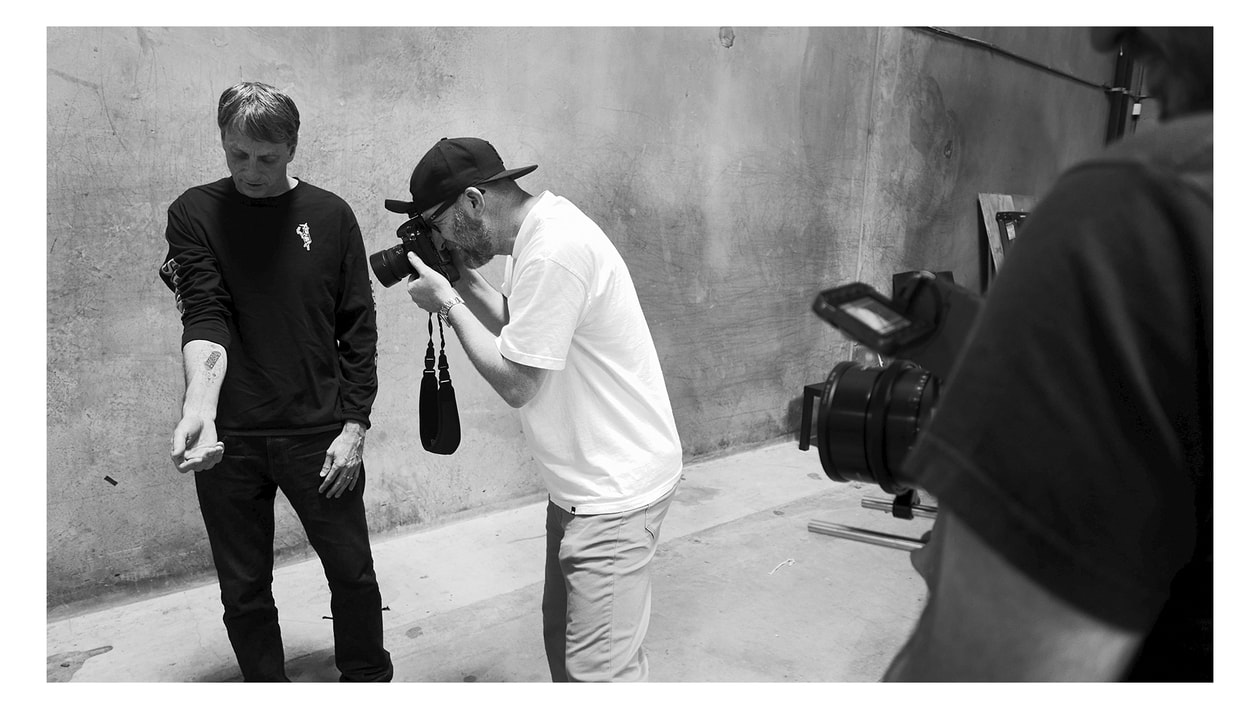

Tony Hawk, Blabac. Photo: Rosenberg.

That’s rad. Do you have any plans on doing more work like this in the future?

I definitely have more things to say about skateboarding. I have a book that I’m working on that’s a bit of a mashup of my photography, artifacts, my correspondences with skaters, and interviews with skaters. It’s kind of reflections of what that time meant for me and how I discovered my voice. Skateboarding was really the way I felt value as a human, truly for the first time. And I think that everyone who has gotten something from skateboarding has gotten that same thing, because inherently you fail in order to succeed. You’re an outsider who becomes an insider in this heavily policed culture. You feel fortunate; you feel lucky.

“I’ve been chosen!”

Yeah. There are more stories in the world of skateboarding that I want to tell, I’m just very selective about those and they’re very personal to me. But they matter and, to me, it’s important to me that I articulate them.

Follow Jacob Rosenberg for updates on his upcoming projects and visit The Reserve Label to see his extensive portfolio.

Mike Blabac’s Family Portraits will be available on December 8. He is currently accepting preorders at his Etsy store.